Table of Contents

by Dr. Albert Bates

Over the last two years, profitability levels in distribution have been at an all-time high. In industries where profit before taxes historically had been at 3 percent of sales it is now at 5 percent or even 7 percent. It is a time for celebration.

Part of the improvement is due to management actions. However, the lion’s share is due to favorable economic conditions. The challenge for distributors is to keep profit at the current high levels as the external factors wane. Without proper actions, profit levels seem destined to regress to the mean. In English, that means back to 3 percent.

Here, we will briefly examine the key external factor that has led to higher profit, then focus on the actions required to maintain profit, and finally, consider what happens if the driver of high profit turns negative.

The Major Driver of High Profit

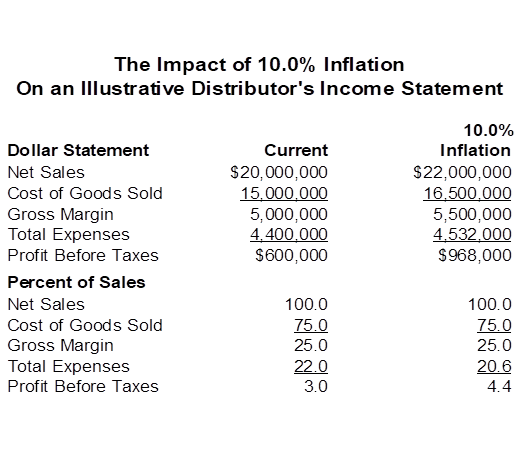

Probably the most hated economic term today is inflation. It is also the key factor that has driven distributor profits to unprecedented levels. The impact of inflation cannot be overstated. Consider a firm with $20. million in sales, a 25 percent gross margin and a long-term pre-tax bottom line of 3 percent. Consider also inflation of 10 percent over the course of a single year

The following exhibit demonstrates the impact of such a high rate of inflation. The exhibit is based upon the actual results produced by distributors as shown in the financial benchmarking reports conducted in various lines of trade. While every line of trade is slightly different, the results reflect the performance of virtually every industry.

As can be seen, sales, cost of goods sold, gross margin all increased by 10 percent due to inflation. As an important note, the exhibit is assuming no actual sales growth. This is done to demonstrate the impact of inflation by itself.

The reality in distribution as shown in the financial benchmarking surveys is that expense increases associated with inflation lagged well behind the increase in sales driven by inflation. For most lines of trade, the inflation-driven increase in expenses was on the order of 3 percent. This represents the “normal” expense changes of the previous few years, while there was the sudden 10 percent increase in sales due to inflation.

The result is that profit before taxes increased by more than 61 percent. It is a massive increase in profit, but one that has little to do with the operation of the organization. It has to do with outside factors, namely inflation.

Absent inflation distributors have not been able to make significant improvements in profitability. For decades, distributors have been stuck with a moderate profit of 3 percent.

This is not to say that distributors have stood idly by while inflation raged. In fact, firms made incredible advances in technology and analytical tools. They continue to do so. It is simply that the changes didn’t have a large impact on performance.

The underlying reason is that distribution is the most competitive sector of the American economy. As one company takes a revolutionary step forward, everyone else rushes forward to copy those steps, making it difficult to get ahead.

What distributors need is a focus on new ways to improve internal operations in a way that actually enhances profitability. Ideally, this new way might not be readily duplicated by competitors. This makes the emphasis is on new ways even more important.

The focus on new ways is also critical for the long term. As inflation goes away, some, if not all, of the benefits of inflation on profit will disappear. This soon will be discussed in greater detail.

Rethinking the Critical Profit Variables

Keeping profit at high levels as inflation wanes requires rethinking the Critical Profit Variables (CPVs). There are three CPVs that are key to maintaining or improving profitability. In practice, these three are combined into two key drivers of profitability.

· Sales Versus Expenses—The challenge of keeping expenses under control while sales increase.

· Gross Margin—The long-standing battle to generate an adequate margin to cover the costs of serving customers.

Distributors control these drivers all of the time, of course. We now will examine some ways that the control efforts can be improved. The goal is to make small, but significant changes that can eventually increase profit dramatically. As will be noted several times, small is not the same as easy.

Sales Versus Expenses

Sales and expenses really need to be examined in conjunction with each other. That is because many of the things that increase sales, such as adding new customers or new products, also increases expenses. Similarly, many expense-reduction programs result in lower sales. The focus needs to be on sales and expenses together.

In developing plans to balance sales and expenses, payroll costs are an obvious priority. Historically, payroll has always comprised about two-thirds of total expenses. That is still true today. As payroll goes, so goes total expenses.

With the help of technology, sales per employee has risen throughout distribution. However, the financial benchmarking surveys in distribution show that over time payroll expenses have grown just as fast as sales. This canceled the positive growth from higher employee productivity. Note that the inflation-based increase in sales is an exception. Eventually, though, payroll will catch up here as well.

The ultimate goal in linking sales and expenses is to have sales grow faster than payroll. This is what is commonly called a sales-to-payroll wedge. Creating a positive sales-to-payroll wedge would seem to be easy to do. Alas, it has proven to be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

There are three focal points for gaining control of payroll:

· Order Economics

· Customer Profitability

· Sales Force Control

Order Economics—Distributors do too much work. Simply put, the average order size is smaller than it should be. Almost every distributor has implemented a minimum order requirement to eliminate the smallest, money-losing orders. Even so, the typical order is still too small to generate adequate profit.

Dealing with the average order size is not an attempt to be more productive. Instead, it is an effort to reduce the work (and payroll) required to generate a given level of sales.

There are two sub-elements in increasing the average transaction size. One is to try to make each line extension on the invoice higher. This is largely a pricing issue and will be discussed in the next section. The second is to put more lines on every order.

The good news is that only a small increase in the number of lines per order is required to dramatically increase profit per order. Strategies include add-on selling, ensuring that customers understand the depth of the product line and actually having items when customers order them.

This last item is especially important. Historically, the number one complaint among customers is that products are not always available when ordered. Supply chain issues briefly made this worse, but service level issues are an on-going problem.

Increasing the average transaction size will automatically raise sales on that individual order. Of much greater consequence it will increase sales at a higher rate than payroll expenses. With more lines, the firm has only a small increase in payroll as the number of orders processed remains the same.

Customer Profitability—Every customer is valuable. It is just that some customers are a lot more valuable than others. Every analysis conducted in distribution suggests that somewhere around 15 percent of the customer base delivers 100 percent of the firm’s profit. At the bottom end of the spectrum, around one-third of all customers are unprofitable, to the tune of lowering dollar profit by about 45 percent.

Surprisingly, it is not that large customers are profitable for distributors and small ones are unprofitable. The main problem is the workload required to generate the sales, regardless of the customer’s size. Unprofitable customers place too many small orders, place too many emergency orders, have too many returns and tie up an inordinate amount of time of sales reps. As a bonus, they often pay slowly.

The key is to work with customers to change their ordering structure if possible. Ideally, the same sales volume could be generated with fewer orders and fewer returns, thereby lowering payroll as a percent of sales. If not, the pricing structure should be changed to cover the cost of servicing high-expense customers.

Sales Force Control—Sales reps have an extremely difficult job. It requires a skill set that few people possess. The result is that there are more people in sales than there than have the proper skills. This means that there are wonderful salespeople in every distributor network, but there are also some who consistently underperform.

The issue is not the terrible sales rep. Those soon depart. The issue is the marginally productive salesperson. The rep that generates 80 percent of the potential in a territory is not costing the firm money. However, that rep is costing the firm the potential profit associated with 100 percent performance. That potential is massive.

The key to working with reps is on-going training. Too often there is the idea that once the rep is trained initially, no further work is required. In reality, there is no such thing as over-training the sales force.

When training doesn’t work, firms need to make the ultimate decision to replace the rep. Understandably, firms are reluctant to do so given the cost of finding a new rep who may come up to speed slowly. From a profit perspective, finding a new rep is a one-time cost. An ineffective sales rep is an on-going cost.

Gross Margin

Gross margin is overwhelmingly a pricing issue. The underlying challenge in pricing is the fear of being perceived as high-priced. Even distributors with great service profiles are haunted by the pricing issue. Distribution is simply too competitive to be saddled with the reputation of not providing fair and equitable prices.

Luckily, from a pricing perspective, all items are not created equally. Every distributor has four groups of items with very different pricing implications:

· A items are price sensitive and make up the bulk of sales volume.

· The term commodities is a disgusting, but often apt, term. Raising prices here is always ill advised given it is where customers build price awareness.

· B and C items are ones with slightly higher margins and sell moderately well, but still have some degree of price sensitivity.

· D items are slow sellers. While margins here may already seem high, they are opportunities for additional price increases.

D items inevitably are bought only when customers have to have them. This means that customers don’t know exactly how much they should cost and, within reason, don’t care. The value added is product availability.

Virtually every distributor is already charging “high prices” on D items. However, price can be increased even more on most D items without hurting the firm’s price perception. It is helpful that D items are often low-price ones. A classic $3.00 D item can be priced at, say, $3.25 and still have a “fair price.” Few customers will shop the item to save the twenty-five cents. This is true as long as the D item is always in stock.

The Mandate for Change

The good news in improving profit is that only a series of small changes need to be made to increase profit sharply. The bad news is that the changes are not easy. The changes are achievable, attainable, doable and realistic. Unfortunately, easy still does not enter the word salad.

For a typical distributor, four illustrative changes would dramatically increase profits:

· Sales—An increase of 5 percent, including both real growth and modest inflation.

· Gross Margin—Increasing the gross margin percentage by 0.2 percent.

· Payroll—Having sales increase 2.0 percent faster than payroll, producing the sales-to-payroll wedge. This is by far the most difficult of the changes, but is still within reach with planning.

· Non-Payroll Expenses—Lowering these by 0.2 percent of sales. If the sales goal is met, this would tend to happen somewhat automatically, remembering that nothing is truly automatic in distribution.

Since all distributors are different, these guidelines must be adjusted for the specific situation. However, these four items are essential as part of the planning process. If something like these changes could be produced, profit could reach a new, higher and potentially sustainable level.

Thinking The Unthinkable: Deflation

We started with a discussion of the impact of inflation on distributor profits. The key point was that inflation helped distributors move from adequate profit levels to unprecedented ones. Firms continued to operate properly, but enjoyed the added benefit of an inflation boost.

As Herbert Stein wisely noted, “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” It appears that inflation at the hyper level has stopped. Stopping is fine, even though the profit kicker will be missed. Inflation turning to deflation—where prices actually start falling—is a long way from fine.

The likelihood of widespread deflation is remote. However, in many industries prices are falling on selected items, especially big-ticket ones. Some perspectives on the profit impact of deflation should be beneficial.

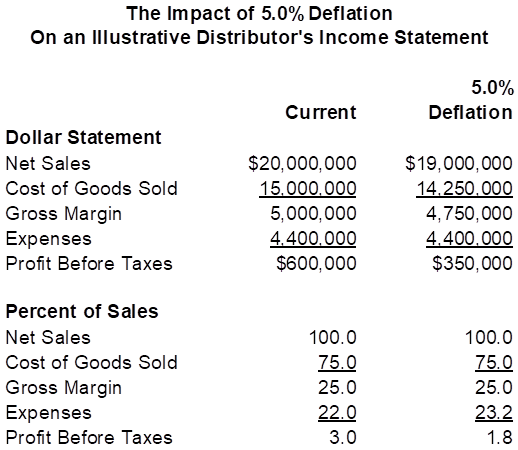

The following exhibit traces the impact of 5 percent deflation which would be a dramatic downward adjustment in prices, but certainly not of the magnitude of the 10 percent inflation rate discussed earlier.

As can be seen in the exhibit sales, cost of goods and gross margin all fall by the same 5.0 percent. Expenses, however, remain constant as their impact in deflation would be delayed for some time.

The result is that profit before taxes falls to 1.8 percent of sales. This represents a decline in dollar profit of 42 percent. It is a significant jolt to the firm.

For once the news is entirely good. If deflation becomes more of an issue, the same solutions that were discussed with regard to improving profit still apply. Namely, the profit-improvement plan still revolves around matching sales with expenses and improving gross margin.

The four points for profit improvement apply in any sort of economy—growth, recession, inflation or deflation. Every distributor should start today to develop such plans.